In an age dominated by artificial intelligence and cloud computing, a surprising number of essential services across the world are still relying on outdated Microsoft Windows systems—some nearly as old as the company itself.

Earlier this year, a trip to a Manhattan doctor’s office revealed an unusual sight. Inside a modern elevator, a familiar relic blinked onscreen: an error message from Windows XP. Though Microsoft ended official support for XP in 2014, the decades-old operating system is still quietly running behind the scenes in hospitals, trains, banks, and even federal agencies.

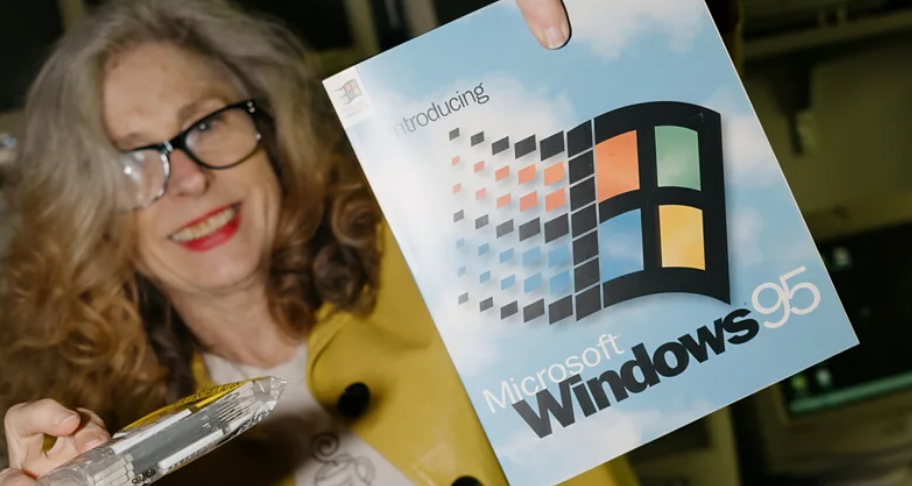

This year marks Microsoft’s 50th anniversary, and while the company is now focused on cutting-edge AI technologies, its legacy software remains deeply embedded in the infrastructure of daily life. “In a way, Windows is the ultimate infrastructure,” says Virginia Tech professor Lee Vinsel. “The fact that we have all of these ancient examples around is the story of the company’s overall success.”

ATMs, for example, are one of the most widespread holdouts. Many still run on Windows XP or even Windows NT, launched in 1993. Elvis Montiero, an ATM technician in New Jersey, explains that upgrades are costly and complicated due to hardware compatibility and regulatory compliance.

Elsewhere, aging software continues to drive mass transit systems. In Germany, a job listing for Deutsche Bahn called for expertise in Windows 3.11 and MS-DOS—technologies more than three decades old. The railway operator explained that some train systems have lifespans exceeding 30 years, and stable legacy software is kept in use for safety and reliability.

San Francisco’s Muni Metro still uses floppy disks to load train control software. And in San Diego, massive LightJet printers for fine art rely on Windows 2000—because upgrading the systems would cost tens of thousands of dollars.

For small businesses and craftspeople, the situation is often similar. Los Angeles woodworker Scott Carlson still runs a CNC machine on Windows XP. “It’s a tank,” he says of the hardware, though the software itself is prone to failure and difficult to replace.

Even in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, outdated technology lingers. Psychiatrist Eric Zabriskie recalls long log-in times and a clunky text-only health records system built on MS-DOS-era code. The VA is now on its fourth attempt to modernize.

Still, for some, old machines are a passion. At Washington State University, Professor Dene Grigar maintains a collection of over 60 vintage computers to preserve early digital literature. “As soon as people got their hands on computers, they started making art,” she says.

Whether out of necessity, cost, or dedication to preservation, the ghosts of Windows past continue to shape the digital present.