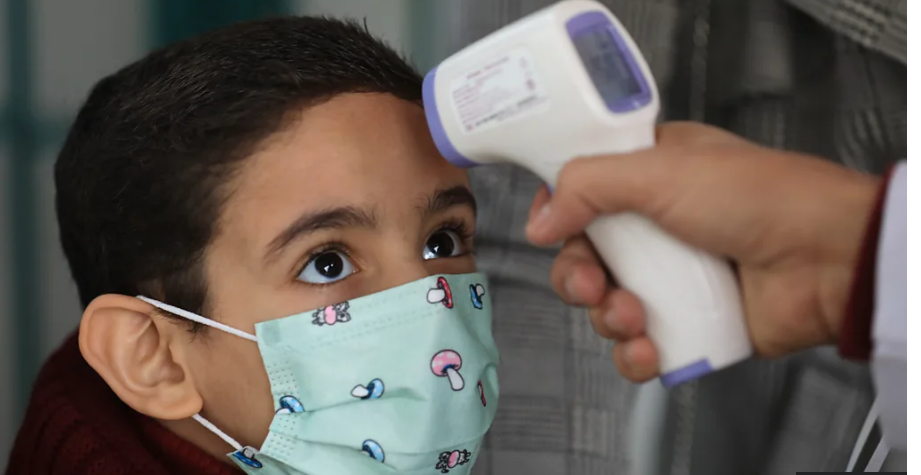

Five years after the COVID-19 pandemic brought global society to a halt, the full toll on children’s development is beginning to emerge. From disrupted learning to delayed social and physical development, researchers and educators are now grappling with the long-term consequences for a generation shaped by lockdowns and isolation.

For Rebekah Underwood, a preschool teacher in Santa Monica, California, the effects are visible daily. The class of 2025, now aged five to six, displays marked differences from their pre-pandemic peers. “Many kids are not able to roll, not able to jump on two feet, they are very hesitant to climb,” she says. These are children who were babies when COVID-19 hit, missing out on crucial early physical and social experiences.

When schools closed in March 2020, 1.6 billion students in more than 190 countries faced interrupted education. With families confined at home, learning was often shifted to parents or screens. Children missed out on playgrounds, music classes, and face-to-face interaction—all fundamental to early development. Even after reopening, many children displayed heightened sensitivity to noise and overstimulation, forcing some schools to pause music instruction altogether.

In the UK, researchers are studying how pandemic-era isolation affected babies born in 2020. The Bicycle study, led by City St George’s, University of London, is tracking the development of children born before, during, and after lockdowns. Preliminary results suggest babies born during lockdowns have weaker language and cognitive skills, possibly due to reduced exposure to social interaction during their critical first year.

Academically, the setbacks are even starker. According to a 2023 U.S. report by the National Academies of Sciences, students across all educational levels are underperforming compared to pre-pandemic norms, with vulnerable populations the hardest hit. A recent global study found that average math scores dropped 14%, equivalent to seven months of learning loss. Some students—especially boys, immigrants, and those from disadvantaged backgrounds—lost even more.

Economists warn that these educational deficits could result in lifelong earnings losses for affected children, with some projections estimating the U.S. economy could lose up to $188 billion annually when these students enter the workforce.

The challenges extend beyond academics. A UK study noted a sharp rise in childhood obesity during the pandemic—an estimated 56,000 additional children became obese, which could cost society an estimated £8.7 billion in long-term health care.

Despite these concerning trends, some experts see opportunity in targeted interventions like tutoring and small-group learning. Yet, the disparities remain. As Judith Perrigo of UCLA notes, the pandemic exacerbated a decline in cognitive and social skills that had already begun. “The COVID pandemic hurt children developmentally,” she says. “But it also accelerated challenges that were already unfolding.”